About

Developed by A. Titus

Easy JavaScript Simulation version by Fremont Teng and Loo Kang Wee

In a contemporary, yet classic survival story, The Martian documents the struggle of astronaut Mark Watney to withstand the barrage of life-ending threats thrown by Mars. Although science fiction, author Andy Weir weaves physics, astronomy, botany, engineering, and chemistry into the book. One of the topics Weir deftly describes is the challenge imposed by traveling to Mars.

This set of activities focuses on the rocket’s orbit around the Sun, the “ideal” time to launch a rocket, and the initial conditions needed for the rocket to arrive at Mars. Students will determine the time between possible launches to Mars and the time required for the rocket to travel to Mars after launched.

| Subject Area | Mechanics |

|---|---|

| Levels | First Year and Beyond the First Year |

| Available Implementation | Glowscript and Easy JavaScript Simulation |

| Learning Objectives |

Students will be able to:

|

| Time to Complete | 120 min |

There are two factors of Mars exploration explored by this activity:

- The time between launches to Mars. (Relative positions of Earth and Mars is important.)

- The time required to travel to Mars after “leaving” Earth.

The Euler-Cromer method can be used to compute the orbits. Thus, this activity is accessible to introductory physics students who have already modeled constant force motion. However, the activity can be extended for students in intermediate mechanics who might compute the motion of the rocket during launch.

Finding the day to launch and the initial direction to launch requires trial and error. It is possible to change parameters and re-run the simulation. However, it may be desirable to have an interface by which one can adjust the parameters and more easily rerun the simulation. This GlowScript simulation trip-to-Mars shows how you can use a second window to interactively set the initial velocity of the rocket using your mouse to adjust an arrow. Then, you can click a button on the day of launch. However, this kind of interactivity is not built into the attached template and sample code.

JPL’s Horizons web interface can be used to obtain initial velocity and position of Mars and Earth on today’s date. If you do not wish to obtain new data, you can use data obtained on Aug. 29, 2015.

| variable | value |

|---|---|

| m | |

| m/s | |

| m | |

| m/s |

Exercise 1 leads students through the exercise of obtaining this data for whatever date they want.

In Exercise 3, a very important point to make to students is that our initial velocity of the rocket is specified relative to Earth. However, its velocity in the simulation must be relative to the Sun. Therefore, the initial velocity of the rocket when launched is

According to Newton’s law of gravitation, the gravitational force by particle on particle is attractive and directed along a line between the masses with a magnitude

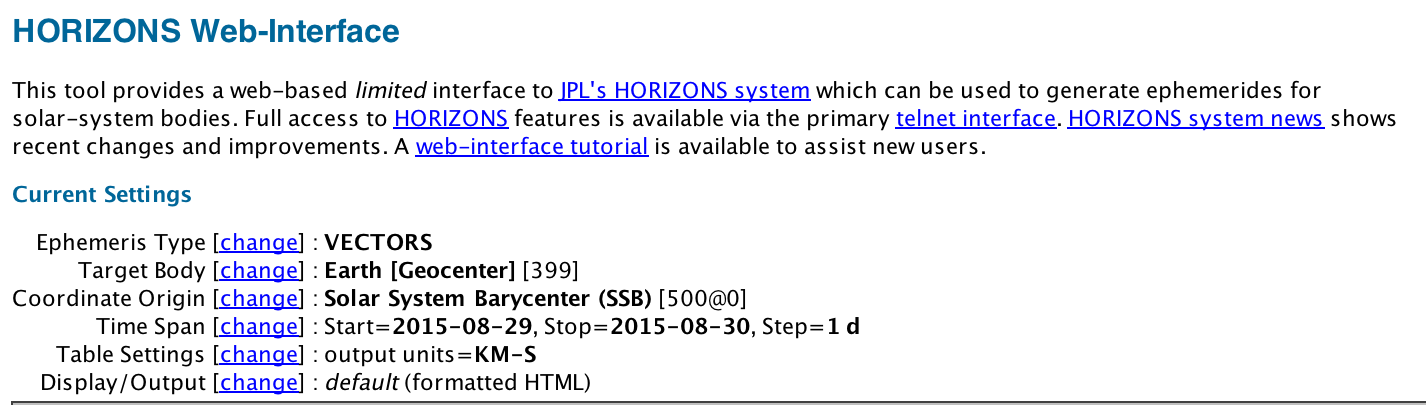

In the first activity, you will determine the time that the relative position of Earth with respect to Mars repeats. This is called the synodic period of Earth and Mars. You will write a simulation of Earth and Mars and will find the time between Earth-Mars-Sun alignment (also called a Mars opposition.)

In the second activity, you will launch a rocket to Mars and measure the time required for the trip.

For a rocket launched to Mars, there are three gravitational forces on the rocket:

During the launch when the rocket is very close to Earth, the dominant forces on the rocket are thrust and the gravitational force by Earth. However we only want to study the gravitational forces on the rocket after it runs out of fuel and is orbiting the Sun. Therefore, we should start our simulation of the rocket when there is no thrust and the rocket is sufficiently far from Earth.

EXERCISE 1

Write a simulation of Mars and Earth orbiting the Sun. You can neglect the interaction of Earth and Mars and only calculate the gravitational force by the Sun on each planet.

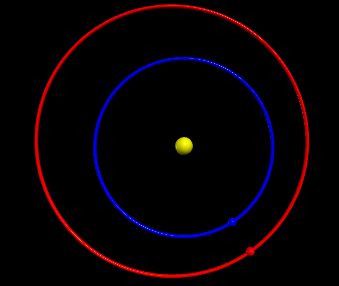

For the initial positions and velocities of the planets in your simulation, use JPL’s Horizons web interface. Here are the instructions for using Horizons.

-

Change the Ephemeris Type to “Vector Table” and click the “Use Selection Above” button to submit the change.

-

Change other settings too until you get the settings shown below (with the particular time span you are interested in).

-

Click the button “Generate Ephemeris.” Record the initial position vector and velocity vector in Cartesian coordinates for Mars. Note the units because you might use meters and seconds in your simulation.

-

Change the “Target Body” to Earth and repeat. Record the initial position vector and velocity vector in Cartesian coordinates for Earth. We will do a 2D simulation, so set the z-components of the position and velocity to zero.

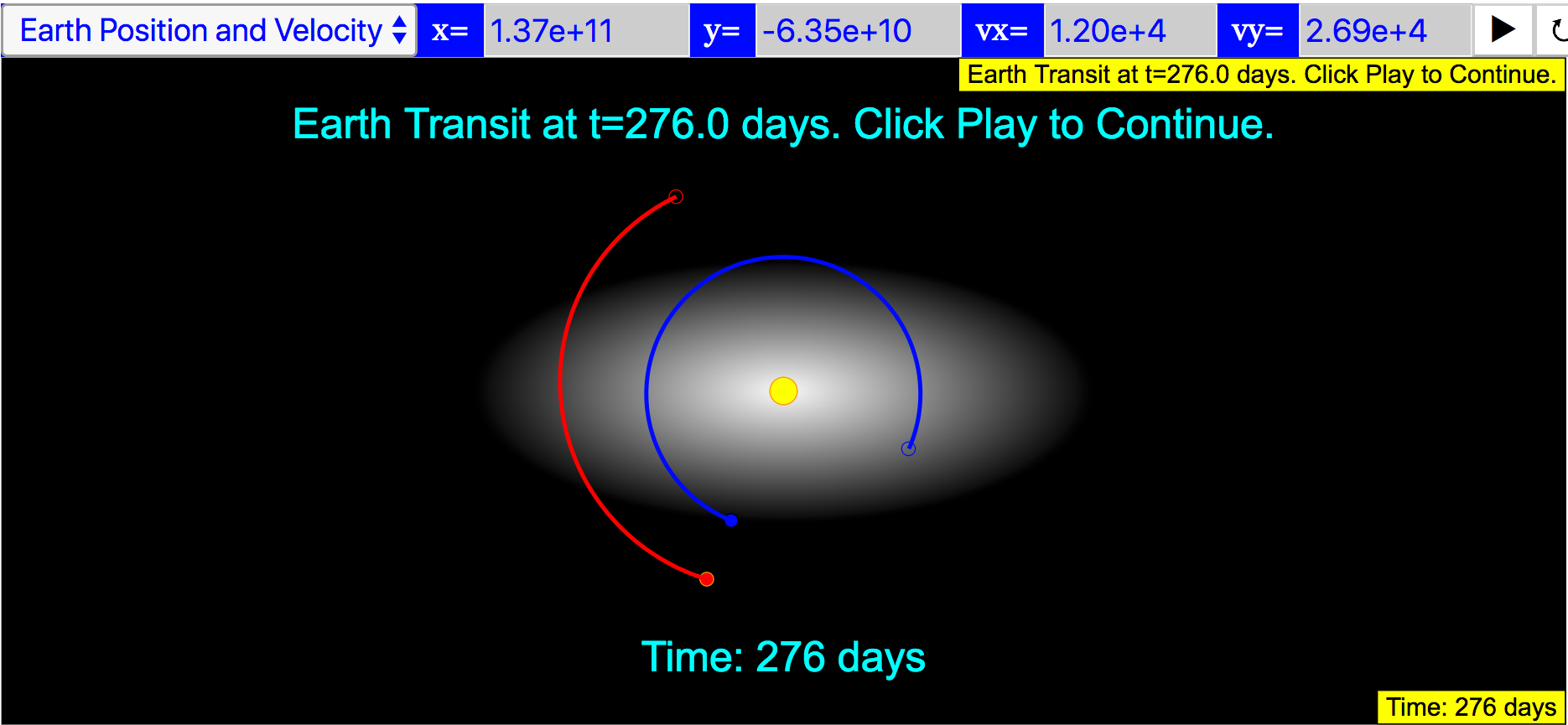

Run your simulation and use it to determine the time (in days) between Mars oppositions, as shown below.

In Exercise 2, you will find the best time (i.e. best relative positions of Earth and Mars) to launch the rocket from Earth. Do you think the best time (best positions of Earth and Mars) is when they are in opposition as shown above? After Exercise 3, you will be able to judge your answer.

EXERCISE 2

You will eventually add a rocket to the simulation you wrote in Exercise 1, and you will find the direction of launch and day of launch that takes the rocket to Mars. However, we must first decide on the initial speed and position we should give the rocket.

To find the initial speed, we will assume:

- at some distance (of our choosing) from Earth, the boosters have burned out and we will call this the initial position of the rocket. Let’s choose an altitude equal to a geosynchronous orbit which is (a distance from the center of Earth).

- near Earth, during the launch, the rocket must reach a speed greater than the escape speed. Earth’s escape speed is 11 km/s. To leave Earth and not return, the rocket will have to reach a speed of at least 11 km/s sometime after takeoff.

- our rocket had a speed of 11.5 km/s when it was near Earth’s surface and its final booster burned out; this was at such a high altitude that air resistance is negligible.

Using these assumptions and the Energy Principle, find the speed of the rocket when it is at an altitude of . What other assumptions did you make?

EXERCISE 3

Depending on the particular orbit, it can take from 130 to 330 days to reach Mars. For NASA’s Mars missions, the average travel time is approximately 225 days, or about eight months. This is a long time, so you should definitely pack snacks and movies. The Mayflower took just over two months to cross the Atlantic. The journey to Mars is about four times longer than the Pilgrims’ journey from Europe to North America.

We will not model the rocket as its boosters are firing. Instead, we will set the initial velocity of the rocket as 5.4 km/s at a distance of 5.6 earth radii () from the center of Earth. (This is an altitude of from Earth.) Then we will try various launch days and launch directions for the rocket at this distance from Earth.

In writing your simulation, use the following assumptions:

- The initial position of the rocket is from the center of Earth. You can place the rocket at any point around Earth because the distance from Earth is small compared to the entire orbit of the rocket. Where on Earth it is launched should have a small effect.

- The speed of the rocket at an altitude of 4.6 Earth radii is 5 km/s. You can set the direction to be any direction you choose. Let this be the rocket’s initial velocity. This speed is chosen because it ensures that the rocket was able to escape from Earth and is sufficiently far from Earth at the beginning of the simulation.

- The thrusters are off during the entire flight. The net force on the rocket is the gravitational force by the Sun, Earth, and Mars.

Find a direction for the initial velocity of the rocket and find a day to launch (using the initial positions of the planets in Exercise 1) such that the rocket travels to Mars. Your program will have to compute orbits for the rocket, Earth, and Mars. You will have to try many different combinations of launch day and launch direction. Use trial and error, but learn from each trial to improve your guesses.

Also, think about what it means to “arrive at Mars.” Does it have to collide with Mars or merely get close enough that rocket boosters could conceivably change the orbit of the rocket?

EXERCISE 4

Try different initial velocities and different days for the launch. Can you find more than one velocity and day that will give an orbit that will work?

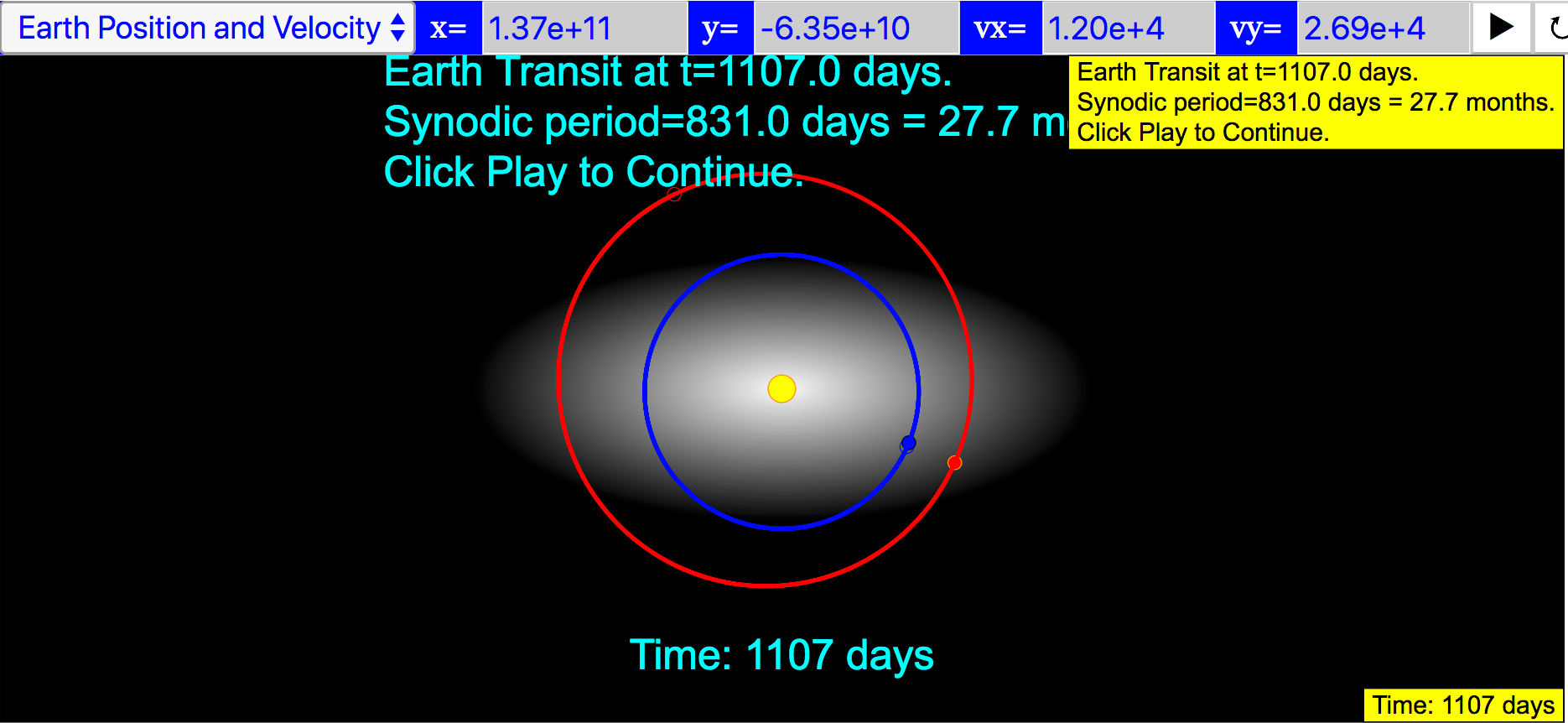

Exercise 1

Using

initial positions on Aug 29, 2015, the first opposition occurs after 276 days. The second opposition is at Day 1107.

The second opposition is at Day 1107.  The

difference is 831 days, which is approximately 27.7 months.

The

difference is 831 days, which is approximately 27.7 months.

Exercise 2

The mass of Earth is kg. Its radius is m. The rocket is initially close to Earth so . Use the Energy Principle to find the speed of the rocket at . Define the system to be Earth and rocket. Assume there is no work or heat transferred to the system. Also, assume that the rocket’s interactions with the Sun and Mars are negligible during this change in altitude from Earth.

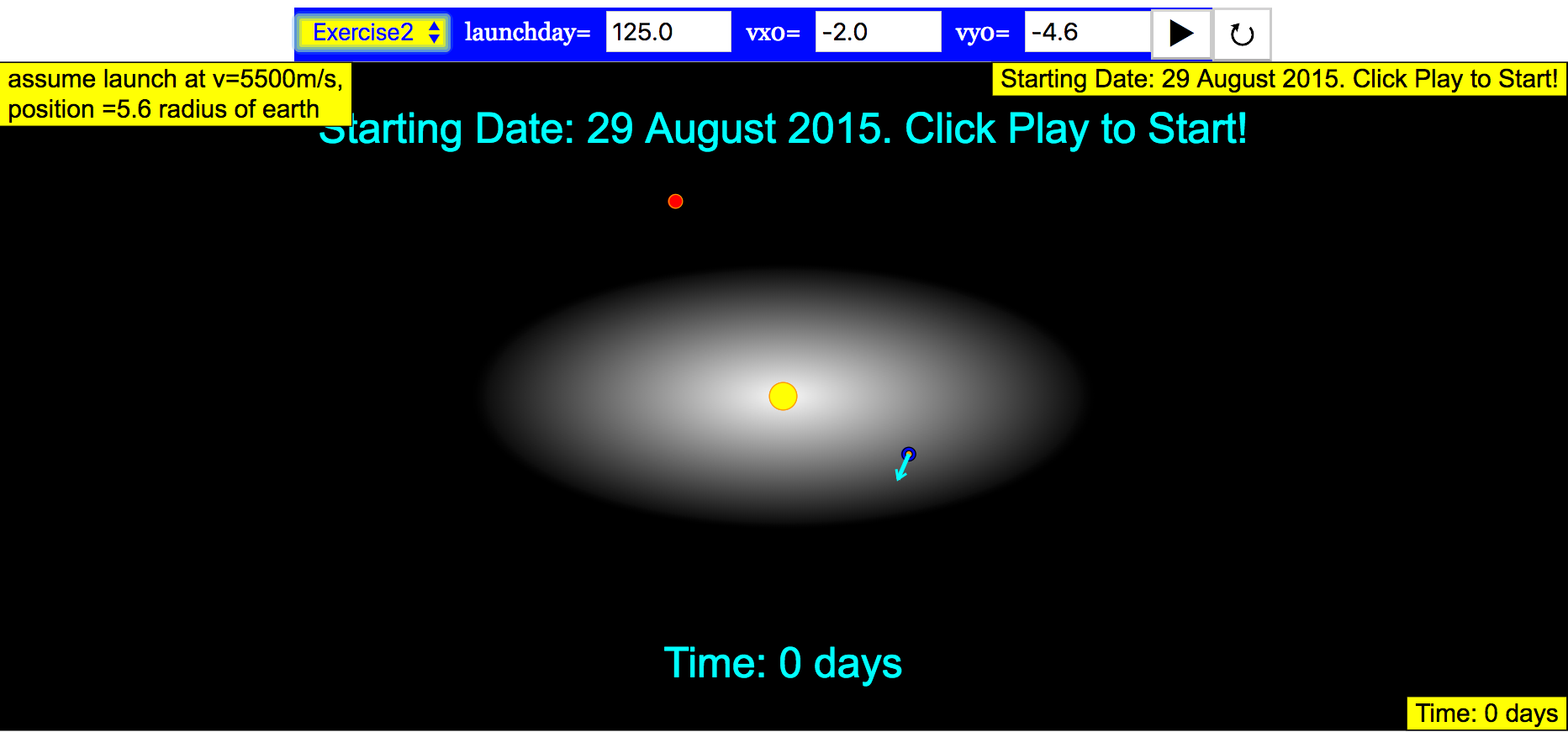

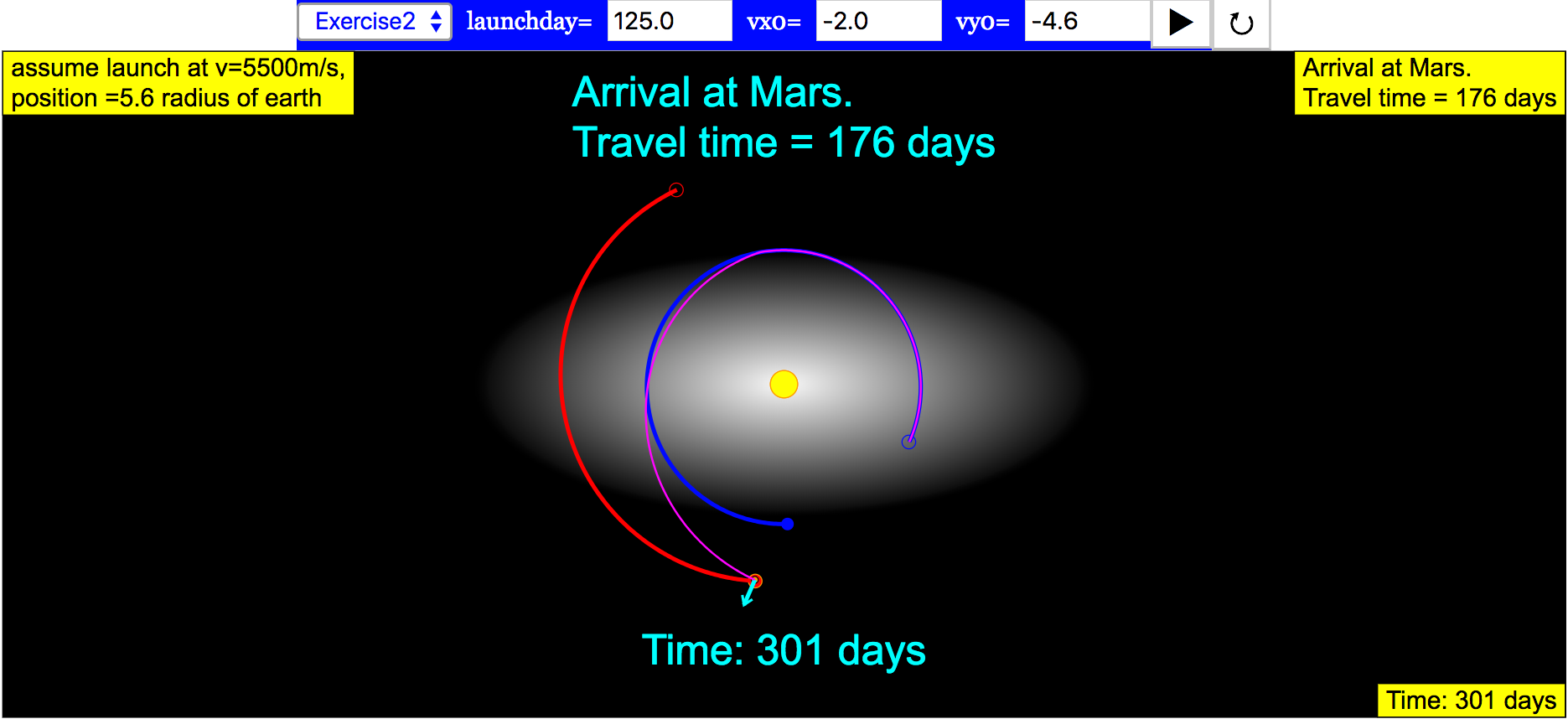

Exercise 3

The completed code uses initial positions on Aug 29, 2015. In this simulation, a possible launch is at Day 125, which is Jan. 01, 2016. Here is the starting point of the simulation.

The rocket arrives on June 25, 2016. This gives a travel time of 176 days which is approximately 6 months. The arrival is shown below (although “arrival” is defined as being within 200 Mars diameters.)

It is worth comparing this result to actual missions. Space.com has an article that gives the following travel time for Mars missions.

| Mission | Travel Time |

|---|---|

| Mariner 4, the first spacecraft to go to Mars (1964 flyby) | 228 days |

| Mariner 6 (1969 flyby) | 155 days |

| Mariner 7 (1969 flyby) | 128 days |

| Mariner 9, the first spacecraft to orbit Mars (1971) | 168 days |

| Viking 1, the first U.S. craft to land on Mars (1975) | 304 days |

| Viking 2 Orbiter/Lander (1975) | 333 days |

| Mars Global Surveyor (1996) | 308 days |

| Mars Pathfinder (1996) | 212 days |

| Mars Odyssey (2001) | 200 days |

| Mars Express Orbiter (2003) | 201 days |

| Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (2005) | 210 days |

| Mars Science Laboratory (2011) | 254 days |

There are many solutions to this problem and it’s hard! Defining a large region of success for “reaching” Mars (like a radius of 500 Mars Diameters) is helpful.

Exercise 4

It is best to collect data from the class on all of their successful orbits.

GlowScript 2.7 VPython

#Developed by A.Titus

launchday=125 #day to launch

rinitial=5.6*6.4e6 #initial distance of rocket from center of earth

marsrocketdist=500*6.8e6 #distance from mars considered a success

vinitial=5.4e3 #initial speed of rocket

# v = vinitial*norm(vec(-1.7,-4.6, 0)) strangely EJSS values does not coincident with glowscript, need to use -1.4 instead of -1.7

v = vinitial*norm(vec(-1.4,-4.6, 0)) #initial velocity of rocket; change the direction only

#pos unit is m

#time unit is s

#pos and vel generated by http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons.cgi

#Aug 29, 2015

#

#no z components

marspos=1000*vec(-1.176389005286295E+08,2.135936464902488E+08,0)

marsvel=1000*vec(-2.027713823922661E+01,-9.661960006152405E+00,0)

earthpos=1000*vec(1.376368513677354E+08,-6.342242292720988E+07,0)

earthvel=1000*vec(1.203162796791987E+01,2.691852057718956E+01,0)

#constants

AU=1000*149597870.7 #AU in m

G=6.67384e-11

#diameters used for drawing sun, mars, and earth; diameters are not to scale

Dsun=0.2*AU

Dearth=0.1*AU

Dmars=0.1*AU

#mass

Msun=1.989e30

Mearth=5.97219e24

Mmars=6.4185e23

Mrocket=1e4

#time

day=24*3600

dt=2*3600

t=0

#set up 3D scene

scene = display(width=430, height=400, userspin=False, userzoom=True)

scene.append_to_title("""<br>Click the simulation to begin.""")

scene.append_to_title("""<br><br>Assumptions include:""")

scene.append_to_title("""<br>1. The rocket's speed near Earth's surface is 12 km/s, relative to Earth.""")

scene.append_to_title("""<br>2. The velocity of the rocket at an altitude of 2 earth radii is 5.4 km/s in the direction shown by the arrow.""")

scene.append_to_title("""<br>3. The thrusters are off during the entire flight. The net force on the rocket is the gravitational force by the Sun, Earth, and Mars.<br><br>""")

#scales for arrows

scale1=Dsun

# set up 3D objects

sun=sphere(dispay=scene, pos=vec(0,0,0), radius=Dsun/2, color=color.yellow)

mars=sphere(dispay=scene, pos=marspos, radius=Dmars/2, color=color.red)

earth=sphere(dispay=scene, pos=earthpos, radius=Dearth/2, color=color.blue)

rocket=sphere( pos=earth.pos+rinitial*norm(v), radius=earth.radius/2, color=color.orange)

rocketarrow1=arrow(dispay=scene, pos=earth.pos, axis=scale1*norm(v), color=color.white)

# create trails

marstrail=attach_trail(mars, radius=0.2*Dmars, trail_type="points", interval=2, retain=1000)

earthtrail=attach_trail(earth, radius=0.2*Dearth, trail_type="points", interval=2, retain=1000)

rockettrail=attach_trail(rocket, radius=0.2*rocket.radius, trail_type="points", interval=2, retain=1000)

rockettrail.stop

#create strings and labels

tstr="Time: {:.0f} days".format(0)

tlabel=label(pos=vector(0,1.2*mag(marspos),0), text=tstr)

launchstr="Starting Date: Aug. 29, 2015. \n"+launchday+" days until launch. \n Click to Run."

launchlabel=label(pos=vector(0,-1.2*mag(marspos),0), text=launchstr)

#set the range

scene.range=1.5*mag(marspos)

#this function is called when the rocket is launched

# it sets booleans and sets the initial velocitiy and momentum of the rocket

def launchRocket():

global vrocket, procket, rocketLaunched, justNowLaunched

rocketLaunched=True

justNowLaunched=True

vrocket=vearth+v

procket=Mrocket*vrocket

# initial positions, velocities, and momenta of all objects

earth.pos=earthpos

rocket.pos=earthpos

mars.pos=marspos

vearth=earthvel

vrocket=earthvel+v

vmars=marsvel

pearth=Mearth*vearth

pmars=Mmars*vmars

procket=Mrocket*vrocket

#booleans

rocketLaunched=False

run = False

justNowLaunched=False

# pause and then change the message

scene.waitfor('click')

launchstr="Launch Day "+launchday

launchlabel.text=launchstr

while True:

rate(200)

#earth

r=earth.pos-sun.pos

rmag=mag(r)

runit=norm(r)

Fearth=-G*Msun*Mearth/rmag**2*runit

pearth=pearth+Fearth*dt

vearth=pearth/Mearth

earth.pos=earth.pos+pearth/Mearth*dt

#mars

r=mars.pos-sun.pos

rmag=mag(r)

runit=norm(r)

Fmars=-G*Msun*Mmars/rmag**2*runit

pmars=pmars+Fmars*dt

mars.pos=mars.pos+pmars/Mmars*dt

#rocket

# launched, then compute Fnet, procket, and rocket.pos

if(rocketLaunched):

rocketarrow1.visible=False

#F by earth

r=rocket.pos-earth.pos

rmag=mag(r)

runit=norm(r)

Frocket_earth=-G*Mrocket*Mearth/rmag**2*runit

#F by sun

r=rocket.pos-sun.pos

rmag=mag(r)

runit=norm(r)

Frocket_sun=-G*Mrocket*Msun/rmag**2*runit

#F by mars

r=rocket.pos-mars.pos

rmag=mag(r)

runit=norm(r)

Frocket_mars=-G*Mrocket*Mmars/rmag**2*runit

#Fnet

Fnet=Frocket_sun+Frocket_earth+Frocket_mars

procket=procket+Fnet*dt

rocket.pos=rocket.pos+procket/Mrocket*dt

if(justNowLaunched):

justNowLaunched=False

#if not launched, just make the rocket at earth's position

else:

rocket.pos=earth.pos

#rocketarrow

rocketarrow1.pos=rocket.pos

#update time and label

t=t+dt

tstr="Time: {:.0f} days".format(t/day)

tlabel.text=tstr

#launch rocket on the launch day

if(t/day>launchday and rocketLaunched==False):

launchRocket()

#arrival at Mars

if(mag(rocket.pos-mars.pos)<marsrocketdist):

launchstr="Arrival at Mars. \nTravel time = {:.0f} days".format(t/day-launchday)

launchlabel.text=launchstr

scene.waitfor('click')

Translations

| Code | Language | Translator | Run | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

Credits

Fremont Teng; Arron Titus; Loo Kang Wee

1. Overview:

This document provides a briefing on the "PICUP Real World Data NASA Travelling to Mars JavaScript Simulation Applet HTML5" resource, developed by A. Titus and adapted for Easy JavaScript Simulation by Fremont Teng and Loo Kang Wee. This open educational resource focuses on the physics behind a mission to Mars, drawing inspiration from Andy Weir's novel The Martian. It offers interactive simulations and exercises designed for first-year and beyond introductory physics students to explore the challenges of interplanetary travel. The primary objectives are to understand the timing of Mars launches and the trajectory of a rocket to Mars.

2. Main Themes and Important Ideas:

The resource revolves around two central themes of Mars exploration:

- The Time Between Launches to Mars: This theme emphasizes the crucial role of the relative positions of Earth and Mars in determining viable launch windows. The resource aims to help students understand why NASA waits approximately 26 months between launch opportunities to Mars.

- The Time Required to Travel to Mars After Leaving Earth: This theme focuses on the orbital mechanics of a spacecraft journeying from Earth to Mars, exploring the initial conditions needed for a successful trajectory and the duration of the voyage.

Key concepts and ideas explored within these themes include:

- Orbital Mechanics: The simulation utilizes Newton's Second Law and the Law of Gravitation to model the orbits of Earth, Mars, and a potential rocket around the Sun. Students are tasked with computing these orbits.

- Synodic Period and Mars Opposition: The resource introduces the concept of the synodic period, which is the time it takes for the relative positions of Earth and Mars to repeat. Students will simulate the orbits to find the time between Earth-Mars-Sun alignments, also known as Mars oppositions.

- Launch Windows: The activities demonstrate why there are optimal times to launch a rocket to Mars based on the planets' positions, leading to the approximately 26-month interval between launch opportunities. Exercise 1 aims for students to "demonstrate why NASA waits approximately 26 months between launches to Mars."

- Initial Conditions: The resource highlights the importance of the rocket's initial velocity (both speed and direction) relative to the Sun for achieving a Mars trajectory. Exercise 3 emphasizes that "our initial velocity of the rocket is specified relative to Earth. However, its velocity in the simulation must be relative to the Sun." The crucial formula provided is:

- "v ⃗ r o c k e t r e l a t i v e S u n = v ⃗ r o c k e t r e l a t i v e E a r t h + v ⃗ E a r t h r e l a t i v e S u n ." (1)

- Gravitational Forces: The simulation considers the gravitational forces exerted by the Sun, Earth, and Mars on the rocket during its interplanetary journey.

- Energy Principle: Exercise 2 applies the Energy Principle to calculate the initial speed required for the rocket to escape Earth's gravity and reach a certain altitude.

- Trial and Error in Trajectory Planning: Finding the correct launch day and initial direction for a Mars mission involves experimentation and iterative adjustments within the simulation. The text notes, "Finding the day to launch and the initial direction to launch requires trial and error."

- Defining "Arrival" at Mars: The resource prompts students to consider what constitutes a successful arrival at Mars, whether it requires a direct collision or just getting close enough for orbital adjustments.

3. Exercises and Learning Objectives:

The resource is structured around four main exercises, each with specific learning objectives:

- Exercise 1: Focuses on simulating the orbits of Earth and Mars around the Sun to determine the time between Mars oppositions. Students will learn to:

- "obtain Cartesian coordinates for Earth and Mars (relative to the Sun) on a given date."

- "use Newton’s Second Law to compute the orbits of Earth and Mars."

- "demonstrate why NASA waits approximately 26 months between launches to Mars."

- Exercise 2: Addresses the initial speed required for the rocket to leave Earth's orbit. Students will learn to:

- "use the Energy Principle to compute the speed of the rocket at a given distance from Earth."

- Exercise 3: Involves simulating the rocket's trajectory to Mars by adjusting the launch day and initial velocity direction. Students will learn to:

- "compute the orbit of the rocket using an initial velocity of the rocket when it is already well above Earth’s atmosphere."

- "find initial conditions that takes a rocket to Mars and measure the time of travel for the rocket."

- Exercise 4: Encourages further exploration of different launch parameters to find multiple successful Mars trajectories.

4. Methodology and Tools:

The resource utilizes:

- Easy JavaScript Simulation (EJS): This platform allows for the creation of interactive physics simulations accessible through web browsers.

- GlowScript: An alternative implementation of the simulation is also available in GlowScript, offering interactive adjustments of initial velocity using a mouse.

- JPL’s Horizons Web Interface: Students are instructed to use this tool to obtain real-world initial position and velocity data for Earth and Mars on a given date for their simulations. The resource provides specific instructions on how to use Horizons, advising to "Change the Ephemeris Type to “Vector Table” and click the “Use Selection Above” button..."

- Euler-Cromer Method: This numerical method is suggested for computing the orbits, making the activity accessible to introductory physics students familiar with constant force motion.

5. Key Findings and Solutions (from the source):

The resource provides some example solutions to the exercises:

- Exercise 1: Using data from August 29, 2015, the simulation finds that the time between Mars oppositions (the synodic period) is approximately 27.7 months (831 days). The first opposition occurred after 276 days, and the second at Day 1107.

- Exercise 2: Using the Energy Principle and given assumptions about the rocket's speed near Earth's surface and altitude after booster burnout, the calculated speed of the rocket at an altitude of 4.6 Earth radii is approximately 5400 m/s.

- Exercise 3: One successful simulation using initial positions from August 29, 2015, shows a launch on Day 125 (January 01, 2016) resulting in an arrival at Mars on June 25, 2016, with a travel time of 176 days (approximately 6 months). The resource notes that "arrival” is defined as being within 200 Mars diameters. The achieved travel time is compared to historical Mars missions, which range from 128 to 333 days.

- Exercise 4: The resource suggests collecting data from students on their successful orbit parameters, implying that multiple solutions exist.

6. Significance and Educational Value:

This resource offers a hands-on and engaging way for students to learn about fundamental physics principles in the context of a real-world challenge – traveling to Mars. By performing simulations and analyzing the results, students can gain a deeper understanding of:

- Newtonian mechanics and gravitational forces.

- Orbital dynamics and the concept of launch windows.

- The application of the Energy Principle.

- The complexities involved in planning interplanetary missions.

- The power of computational modeling in physics.

The connection to The Martian provides a relatable and motivating entry point for students. The availability in both Easy JavaScript Simulation and GlowScript formats increases accessibility for different learning environments. The inclusion of exercises that guide students through obtaining real-world data from JPL’s Horizons enhances the authenticity and relevance of the learning experience.

7. Areas for Consideration:

- The trial-and-error nature of finding a successful Mars trajectory in Exercise 3 might be time-consuming for some students. Providing more guidance or starting parameters could be beneficial.

- The definition of "arrival" at Mars (within 200 Mars diameters or later 500 Mars diameters as mentioned in the solutions) should be clearly communicated to students.

- The resource acknowledges that the provided template and sample code lack the interactive velocity adjustment feature present in the linked GlowScript simulation ("trip-to-Mars"). Incorporating similar interactive elements could enhance student exploration.

This "PICUP Real World Data NASA Travelling to Mars JavaScript Simulation Applet HTML5" resource provides a valuable tool for physics educators to engage students in the fascinating science behind space exploration.

Journey to Mars: A Study Guide

Quiz

- What are the two main factors of Mars exploration explored by the PICUP activity?

- According to the text, why is the relative positioning of Earth and Mars important for planning a Mars mission?

- What is the synodic period in the context of Earth and Mars orbits, and what astronomical event is related to it?

- Why does the simulation of the rocket's journey to Mars begin after the boosters have burned out and the rocket is sufficiently far from Earth?

- Explain how students can use JPL's Horizons web interface in Exercise 1, and what specific data should they obtain.

- In Exercise 2, what key assumptions are made to calculate the initial speed of the rocket at a certain distance from Earth using the Energy Principle?

- What is the typical travel time for NASA's Mars missions according to the provided text, and how does this compare to the Mayflower's journey across the Atlantic?

- In Exercise 3, what crucial point is made regarding the initial velocity of the rocket in the simulation compared to its velocity relative to Earth at launch?

- What three gravitational forces are considered to be acting on the rocket during its journey to Mars in the simulation?

- How is "arrival at Mars" defined in the context of the simulation results provided in Exercise 3?

Quiz Answer Key

- The two main factors explored are the time between possible launches to Mars, which depends on the relative positions of Earth and Mars, and the time required for the rocket to travel to Mars after leaving Earth.

- The relative positioning of Earth and Mars is crucial because it determines the "ideal" time to launch a rocket to ensure it can intercept Mars efficiently, minimizing travel time and fuel consumption.

- The synodic period is the time it takes for the relative positions of Earth and Mars to repeat. It is related to Mars opposition, which is when Earth passes between Mars and the Sun.

- The simulation focuses on the gravitational forces acting on the rocket during its interplanetary travel, so it begins after the period when thrust from the boosters is the dominant force and the rocket has escaped Earth's immediate vicinity.

- Students should change the Ephemeris Type to "Vector Table" on JPL's Horizons interface and generate ephemerides for both Mars and Earth to record their initial position and velocity vectors in Cartesian coordinates for a chosen date.

- The key assumptions include that the boosters have burned out at a specific altitude (4.6 Earth radii), the rocket achieved 11.5 km/s near Earth's surface, and that the rocket's interactions with the Sun and Mars are negligible during this phase.

- The average travel time for NASA's Mars missions is approximately 225 days, or eight months. This is about four times longer than the Mayflower's journey, which took just over two months.

- The initial velocity of the rocket is specified relative to Earth, but the simulation requires the velocity to be relative to the Sun. Therefore, the velocity of Earth relative to the Sun must be added to the rocket's velocity relative to Earth.

- The three gravitational forces acting on the rocket in the simulation are the force due to the Sun, the force due to Earth, and the force due to Mars.

- In the provided simulation result, "arrival at Mars" is defined as the rocket being within 200 Mars diameters of the planet.

Essay Format Questions

- Discuss the challenges involved in determining the optimal launch window for a Mars mission, explaining the significance of the synodic period and Mars opposition.

- Explain how the Energy Principle is applied to determine the initial speed requirements for a rocket to escape Earth's gravity and reach a specified altitude for a Mars mission. What are the limitations of this approach?

- Describe the process of simulating a Mars mission, highlighting the key assumptions made and the gravitational forces that must be considered to accurately model the trajectory of the spacecraft.

- Analyze the trial-and-error process involved in finding the correct launch day and initial velocity direction for a rocket to reach Mars in the simulation. What factors make this a complex problem?

- Compare and contrast the simulated Mars mission travel times with historical data from actual Mars missions. What factors might account for any differences observed?

Glossary of Key Terms

- Cartesian Coordinates: A system of coordinates that specifies each point uniquely in a plane by a pair of numerical coordinates, which are the signed distances to the point from two fixed perpendicular oriented lines, measured in the same unit of length. In three dimensions, three coordinates are used.

- Euler-Cromer Method: A numerical method used to solve ordinary differential equations, often employed in physics simulations for its stability in cases involving oscillatory motion, like orbital mechanics.

- Energy Principle: A fundamental principle in physics stating that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant over time. It can be used to analyze changes in kinetic and potential energy.

- Escape Speed: The minimum speed needed for a free, non-propelled object to achieve an infinite distance from a massive body, i.e., to escape its gravitational field. For Earth, it is approximately 11 km/s.

- Geosynchronous Orbit: An orbit around Earth of a satellite with an orbital period that matches Earth's rotational period, appearing stationary when viewed from the ground.

- GlowScript: A web-based 3D graphics environment based on VPython, often used for creating physics simulations that can be run in a web browser.

- Gravity: A fundamental force of nature by which all things with mass or energy—including planets, stars, galaxies, and even light—are brought toward one another.

- Initial Conditions: The set of values for the position and velocity (and sometimes other variables) of a system at the beginning of a simulation or a physical process, which are necessary to determine the system's subsequent evolution.

- JPL's Horizons: An online system provided by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory that can be used to generate ephemerides, which are tables of positions of celestial bodies over time, along with their velocities and other data.

- Mars Opposition: The configuration when Earth passes directly between the Sun and Mars. This occurs approximately every 26 months and is often considered a favorable time to launch missions to Mars due to the closer proximity of the two planets.

- Newton's Second Law of Motion: States that the acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on the object, is in the same direction as the net force, and is inversely proportional to the mass of the object (F=ma).

- Newton's Law of Gravitation: States that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

- Orbit: The gravitationally curved path of an object around a point in space, for example, the orbit of a planet around a star.

- Synodic Period: The time interval between two successive similar alignments of three celestial bodies in their orbits, such as the time between two Mars oppositions as viewed from Earth.

- Velocity Vector: A vector quantity that expresses both the speed and the direction of motion of an object.

Sample Learning Goals

[text]

For Teachers

Travelling to Mars JavaScript Simulation Applet HTML5

Instructions

Control Panel

Play/Pause and Reset Buttons

Research

[text]

Video

[text]

Version:

- https://www.compadre.org/PICUP/exercises/exercise.cfm?I=128&A=marsmission

- http://weelookang.blogspot.com/2018/05/travelling-to-mars-javascript.html

- http://www.glowscript.org/#/user/lookang/folder/Public/program/PICUPmarsmissionexercise1

- http://www.glowscript.org/#/user/lookang/folder/Public/program/PICUPmarsmissionexercise234

Other Resources

Frequently Asked Questions: Travelling to Mars Simulation

- What is the primary goal of this simulation activity? This activity aims to explore the complexities of a mission to Mars, specifically focusing on two key aspects: determining the optimal time intervals for launching a rocket from Earth to Mars and calculating the duration of the interplanetary journey once the rocket has left Earth's vicinity. It allows users to investigate the orbital mechanics involved in such a mission.

- What key physics concepts are involved in simulating a trip to Mars? The simulation heavily relies on Newtonian mechanics, particularly Newton's Law of Gravitation to model the forces between the Sun, Earth, Mars, and the rocket. It also utilizes Newton's Second Law to compute the orbits of the planets and the rocket under these gravitational forces. The Energy Principle is applied to determine the initial speed requirements for the rocket to escape Earth's gravity.

- Why is there a waiting period of approximately 26 months between potential launch windows to Mars? This waiting period is due to the synodic period of Earth and Mars. A successful launch requires the planets to be in a specific relative alignment to minimize travel time and fuel consumption. This favorable alignment, often referred to as a Mars opposition (where Earth passes between the Sun and Mars), occurs roughly every 26 months. The simulation allows users to determine this period by observing the repeating relative positions of Earth and Mars in their orbits around the Sun.

- How does the simulation determine the orbits of Earth and Mars? The simulation models the orbits of Earth and Mars by calculating the gravitational force exerted by the Sun on each planet. It neglects the relatively smaller gravitational forces between Earth and Mars. By using initial position and velocity data (which can be obtained from JPL's Horizons web interface) and applying Newton's Second Law over small time steps (often using the Euler-Cromer method), the simulation iteratively updates the planets' velocities and positions, thus tracing their orbital paths.

- What are the initial conditions considered for launching the rocket in the simulation? The simulation simplifies the initial launch phase by considering the rocket after its boosters have burned out and it is sufficiently far from Earth (at an altitude of approximately 4.6 Earth radii, or 5.6 Earth radii from the center). It sets an initial velocity for the rocket relative to Earth (which then needs to be converted to a velocity relative to the Sun for the simulation) and allows users to experiment with the launch day and direction to find a trajectory that reaches Mars.

- What forces are considered to be acting on the rocket during its journey to Mars in the simulation? Once the simulation of the rocket's interplanetary travel begins, it considers the gravitational forces exerted by the Sun, Earth, and Mars on the rocket. The effects of the rocket's thrusters or any mid-course corrections are not modeled in this simplified simulation. The dominant force for most of the journey is the Sun's gravity.

- How does the simulation define "arrival" at Mars? What is a typical travel time to Mars based on the simulation and real-world missions? The simulation defines "arrival" at Mars as the rocket getting within a certain distance of Mars (in the provided code, this is set to 500 Mars diameters). The simulation results indicate a possible travel time of around 176 days (approximately 6 months) for a successful trajectory starting on Day 125 after the initial date. Real-world Mars missions have experienced travel times ranging from about 128 to over 300 days, with an average of around 225 days (8 months), depending on the specific trajectory and mission objectives.

- What is the role of trial and error in using this simulation to plan a Mars mission? Finding the correct launch day and initial velocity direction for the rocket to reach Mars in the simulation requires significant trial and error. Users can adjust these parameters and rerun the simulation to observe the resulting trajectory. By analyzing why certain attempts fail, users can iteratively refine their guesses for the launch conditions to eventually achieve a successful transfer orbit to Mars. The simulation provides a hands-on way to understand the sensitivity of interplanetary trajectories to initial conditions.

- Details

- Written by Fremont

- Parent Category: 02 Newtonian Mechanics

- Category: 08 Gravity

- Hits: 9284

.png

)